Gov. Phil Scott, often criticized for talking the talk on climate change but not walking the walk, has this session proposed $1.5 million in electric vehicle incentives for low- and moderate-income Vermonters. Environmental advocates applaud the move, but say it’s not enough.

Gov. Phil Scott, often criticized for talking the talk on climate change but not walking the walk, has this session proposed $1.5 million in electric vehicle incentives for low- and moderate-income Vermonters. Environmental advocates applaud the move, but say it’s not enough.

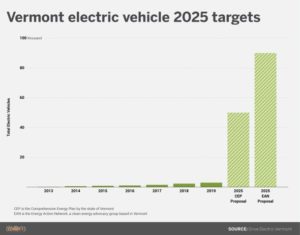

In his budget address at the start of the session, the governor said Vermont needs 10 percent, or around 50,000, electric vehicles on the road by 2025 under goals set in the state’s Comprehensive Energy Plan.

“I don’t believe we can meet those goals unless we help people make this transition,” said Scott.

The cost to fuel electric vehicles is significantly lower than the cost of gas, he said, meaning the transition could save Vermonters millions of dollars in energy costs.

Electric vehicles have been a frequent discussion topic in the transportation committees in both chambers; House Transportation voted favorably last week on a recommendation to bump up electric vehicle incentives to $4.5 million.

State agencies are also working toward increasing the purchase and use of electric vehicles in the state.

The Public Utility Commission last year started investigating how the state and its public utilities can promote electric vehicle ownership without adverse impacts on non-electric vehicle ratepayers. The state has already started doling out $2.4 million in public electric vehicle charging station grants.

And Vermont utilities have started rolling out electric vehicle incentives and special home charging rates. Representatives from Burlington Electric Department and Green Mountain Power testified in front of the Senate Transportation Committee Friday that electric vehicle charging could reduce rates for customers by allowing utilities to spread transmission costs over a larger load.

“The more electrons that we can get out there that are from clean sources, the better,” said Robert Dostis, vice president of customer relations for GMP.

But it’s going to be a heavy lift to get to get to 50,000 electric vehicles in six years. There were 2,985 passenger electric vehicles registered in the state as of January, according to Drive Electric Vermont, meaning the state would need a 1,575 percent increase in electric vehicle ownership in six years.

And environmental advocates say even the state’s lofty goal isn’t enough to meet Vermont’s greenhouse gas emissions reductions targets. Jared Duval, executive director of the Energy Action Network, says the state needs closer to 90,000 electric vehicles by 2025 to meet the Paris Climate Agreement targets in addition to other measures to curb emissions.

“This speaks to the larger challenge that the state’s energy goals and their emissions goals do not align,” he said.

He added that encouraging the switch to electric vehicles and non-fossil fuel heating would keep more money circulating in Vermont’s economy, expanding on the “buy local” notion that has taken off in the food industry.

Johanna Miller, energy and climate program director for Vermont Natural Resources Council, applauded the governor for putting forward an electric vehicle incentive, but added that it’s “a smidgen of what will be required.”

She said Vermont should join Connecticut and Massachusetts in turning its emissions goals into enforceable mandates, which is the aim of a new bill, H.462. Both Duval and Miller said the state also needs an “economy-wide” carbon price or cap and invest policy to generate revenue to reinvest in cleaner technologies and decrease emissions.

“You look at our electric sector,” said Miller. “It’s not by accident that our greenhouse gas emissions have gone down in that sector.”

Rep. Brian Savage, R-Swanton, was one of two members of the House Transportation Committee who voted against the recommendation to provide $4.5 million in electric vehicle incentives.

Savage said in general he was not a fan of using incentives to drive consumer change, but that he didn’t have a problem with the governor’s proposal to direct money from the attorney general’s settlement fund toward electric vehicle incentives. Adam Greshin, commissioner of finance and management, said there was more money available in that fund than had been in past years because of the Volkswagen and other settlements received in fiscal year 2019.

“We don’t see where the extra $3 million is,” said Savage. “I voted no because we don’t have the money.”

He added that he didn’t think the goal of 50,000 electric vehicles by 2025 was realistic.

Peter Walke, deputy secretary of the state Agency of Natural Resources, said that the administration has “put a proposal on the table that we think helps start the work that needs to be done.”

Matt Cota, a fuel industry lobbyist, said that, for the first time in the 12 years he has lobbied in the Statehouse, there is a serious discussion in relevant committees to prepare for “what is seen by what seems like a majority of policymakers” to be a coming switch to non-combustion vehicles.

He said the question on his clients’ minds is whether there is a space in that transition for gas station owners, adding that some have already started offering charging stations.

“In my opinion, the answer is yes,” he said. “But it is different, with 80 percent of those people filling their proverbial gas tank at home.”

“What they’re not for is a tax on their fuel to pay for their competitors’ fuel,” he added, referring to carbon tax proposals that surfaced earlier this week.

Link to Original VT Digger Post. Article by Elizabeth Gribkoff,